The idea for this reflection began over a conversation with a close friend. We were brainstorming business ventures – small, quick flips all the way up to more ambitious, long-term projects. My friend kept gravitating toward the smaller, more predictable ones. The kind that guarantees immediate returns. That observation sparked something: it wasn’t that he lacked patience. He was perfectly happy to wait. It was the uncertainty of the outcome that was doing the work.

That realization became the foundation of everything that followed.

My friend was okay with spending six months flipping bikes for a $200 profit each, but he won’t spend six months building an app people might actually use. Same time horizon. Same person. Completely different commitment level.

The conventional explanation is that he lacks the ability to delay gratification – he prefers quick wins over building something substantial. But that explanation falls apart under examination. He’s willing to wait six months for the bike operation to pay off. Patience isn’t the variable. Certainty is.

The Real Barrier

We’ve misdiagnosed the problem. When people choose immediate small rewards over delayed large rewards, we assume they can’t wait. But delayed gratification only works when the future reward feels believable.

The real barrier isn’t time. There is uncertainty about whether the wait will actually pay off.

Your brain doesn’t resist waiting. It resists unclear probabilities.

Why Our Brain Works This Way

This wiring runs deep, but not in the way we usually describe it.

The standard explanation (provided by Daniel Kahneman) invokes loss aversion and evolutionary survival pressures. That’s all true. But there’s a more specific mechanism at work here: the brain’s ability to model feedback loops. Ancestral humans didn’t just prefer certainty in the abstract; instead, they survived by building accurate models of cause and effect.

Action → result. Plant here → harvest there.

The mental architecture that got us this far is fundamentally a pattern-matching engine calibrated for legible feedback.

That engine works well in stable environments. The challenge starts when feedback is delayed, and more variables are added into the equation. Trust me, everyone is smart and understands the risks and challenges in a venture. However, their brain hasn’t experienced an unmodeable system, and it just goes silent. The anxiety wasn’t fear of loss; instead, it was the inability to run the multiple if-then simulations and visualize them.

The “Glorified Gig” Pattern

Most of us want to control every moment and believe that a side gig can solve the problem. This explains why smart, ambitious people gravitate toward small-scale ventures with tight feedback loops: Bike flipping, ride-sharing, furniture restoration, or Small consulting projects.

These aren’t chosen because people lack patience, but they can easily visualize the outcome. You buy a bike for $50, spend three hours cleaning it, and sell it for $250. If it fails, you know why. If it succeeds, you know why. The variables are few and mostly within your control.

The pattern holds as scale increases:

- Bike flip: tiny capital, short cycle, few controllable variables

- House flip: larger capital, longer cycle, more semi-controllable variables

- Corporate incremental bets: massive capital, long cycles, predictable models

What increases isn’t just time or money. It’s the number of variables your brain can no longer run a clean simulation on.

But Then There’s the Other Pattern

Some ventures don’t fit this logic, such as startups, creative careers, or novel architecture proposals.

These paths have long timelines, uncertain feedback, and outcomes driven by factors you can’t fully control: market timing, competition, user behavior, and luck. By every rational measure, they should trigger the same uncertainty aversion. Yet people pursue them all the time.

Two Ways People Deal With Uncertainty

Some people respond to uncertainty by staying within zones where outcomes feel modelable. Others deal with it by mentally reframing the risk.

The aspiring founder thinks: I’ll work hard, build something good, and it will work. They have turned uncertainty into perceived certainty by believing in their own effort and ability. The statistics apply to others. You may see this everywhere:

- Startup founders leaving stable jobs

- Authors writing novels for years

- Aspiring actors moving cities

- Athletes chasing pro careers

The actual uncertainty is enormous. The perceived certainty is high. This isn’t self-deception exactly → it’s a functional illusion that makes action possible.

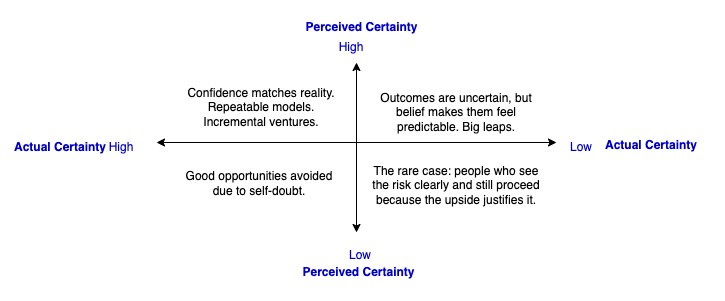

Perceived Certainty vs. Actual Certainty

The key difference isn’t just risk tolerance; it is all about the gap between how uncertain something truly is and how uncertain it feels. Two dimensions shape most decisions:

- Actual certainty → How predictable the outcome really is

- Perceived certainty → How predictable the outcome feels to you

That creates four general patterns be captured in a 2×2 matrix:

Most of us live in the top row. We either choose things that are genuinely predictable, or we convince ourselves they are.

How Corporations Institutionalize the Top-Left

Large organizations overwhelmingly anchor themselves in the first quadrant. Not because the people inside lack imagination, but because the system self-select a decisions that look certain on paper.

Any bold idea that makes it to a committee must appear as a forecast. It is not because anyone is trying to mislead, but because the system runs on numbers. That’s the only common format that allows different ideas to be compared.

Uncertainty must be translated into projections before a budget moves forward. That’s simply how decisions get made. Executives need a consistent way to evaluate everything on the table. So the numbers aren’t dishonest, but they’re structural. Having said this in this journey, something subtle gets washed away – the clear acknowledgment that we are operating in territory no one actually understands yet.

What fades isn’t integrity, but it is the acknowledgment that this is still unknown ground.

One of the classic ways organizations end up pursuing transformation while funding only incremental change, only to be disrupted by a start-up (a similar idea is captured here). The language says “moonshot”, but the spreadsheet says “1.3x revenue with 12-month payback.” The committee approves the one that fits the model it already knows how to evaluate.

The result isn’t a lack of courage. It’s something more subtle: a collective mechanism for converting the bottom-right quadrant into the top-left, so the decision feels manageable, even when the situation isn’t.

The Marshmallow Test

The famous marshmallow test wasn’t just about patience. It was about whether the child believed the adult would return with the second marshmallow.

It wasn’t, can you wait? It was do you believe the promised future is real?

The Rare Few

Most people who make big bets belong in the top-right: they’ve convinced themselves it will work. That confidence is necessary fuel. But it’s not the most interesting case.

The bottom-right quadrant is where it gets philosophically uncomfortable. These are the people who look at the odds clearly, believe they probably apply, and proceed anyway. What makes them different isn’t delusion or bravado. It’s usually one of three things:

- Some have decoupled their identity from the outcome. They aren’t pursuing the goal because they expect to win, but they are pursuing it because the work itself has intrinsic value. The novelist who spends seven years on a book she knows might not find a publisher isn’t ignoring the odds. She’s just decided that the writing matters independent of what happens to it. Uncertainty is still real. It just has less leverage over her.

- Some have done the expected value math and accepted the conclusion. The venture is unlikely to work, the payout if it does work is extraordinary, and the cost of not trying is higher than the cost of failing. This isn’t a gut call. It’s arithmetic with honest inputs – including a realistic failure probability.

- And some simply have a longer time horizon than the uncertainty warrants. They’re not betting on a specific outcome. They’re betting on a direction. The variance is high in any given year, but the drift is predictable enough over a decade.

What all three have in common: they’re not flinching from the bottom-right quadrant. They’re operating there deliberately. In my own journey, I’ve learned to function more from the first two approaches.

The Real Question

We have been asking the wrong question. The question has usually been:

“Can you delay gratification?” But that’s not really what’s going on.

The deeper question is: “How do you deal with uncertainty, especially the kind you can’t mentally model, predict, or reason away”.

Waiting is easy when the future feels guaranteed. The interesting behavior happens when the equation looks like this: invest time, money, and effort into an outcome you can’t confidently simulate.

Some people walk away. Some convince themselves that the odds don’t apply. A rare few see the uncertainty clearly, decide the terms are still acceptable, and act.

What we call courage is often just a different relationship to not knowing how it ends.